How Go was made

GopherCon Closing Keynote

9 July 2015

Andrew Gerrand

Andrew Gerrand

A video of this talk was recorded at GopherCon in Denver.

2How was Go made?

What was its development process?

How has the process changed?

What is its future?

Robert Griesemer, Rob Pike, and Ken Thompson's thought experiment:

"What should a modern, practical programming language look like?"

5Design discussions by mail and in-person.

Consensus-driven:

A feature was accepted only when all the three authors agreed it necessary.

Most proposed changes were rejected.

6The first artifact of Go was the language specification.

The first commit (now git hash 18c5b48) was a draft of that spec:

Author: Robert Griesemer <gri@golang.org>

Date: Sun Mar 2 20:47:34 2008 -0800

Go spec starting point.Go's entire history is preserved in the core reposistory.

7The first Go program was a Prime Sieve, and was included in the spec.

func Filter(in *chan< int, out *chan> int, prime int) {

for {

i := <in; // Receive value of new variable 'i' from 'in'.

if i % prime != 0 {

>out = i // Send 'i' to channel 'out'.

}

}

}

func Sieve() {

ch := new(chan int); // Create a new channel.

go Generate(ch); // Start Generate() as a subprocess.

for {

prime := <ch;

printf("%d\n", prime);

ch1 := new(chan int);

go Filter(ch, ch1, prime);

ch = ch1

}

}

Subversion was the project's first version control system. (no code review!)

The trio made 400 commits to Subversion.

The last Subversion commit (git hash 777ee7, 21 July 2008) contained:

test/helloworld.go:

package main

func main() {

print "hello, world\n";

}

In July 2008 the project migrated from Subversion to Perforce,

to use Google's excellent code review system.

The team grew:

It was easy to make changes in those days.

Everyone knew each other.

There were ~0 users.

All the source code in one place.

Workflow informal, but design-oriented.

11Many problems don't have obvious solutions.

The team were prepared to wait until they found the correct design.

For example:

The fmt package was written long before reflect.

Before then, fmt had an awkward chaining API:

fmt.New().s("i = ").d(i).putnl()Now:

fmt.Println("i = ", i)Another example:

Slices took more than a year to figure out.

Before then, there were "open arrays" but they were awkward.

src/lib/container/vector.go @ f4dcf51:

// BUG: workaround for non-constant allocation.

// i must be a power of 10.

func Alloc(i int) *[]Element {

switch i {

case 1:

return new([1]Element);

case 10:

return new([10]Element);

case 100:

return new([100]Element);

case 1000:

return new([1000]Element);

}

print "bad size ", i, "\n";

panic "not known size\n";

}

chan and map were originally spelled *chan and *map.

The team had a meeting to discuss removing the asterisks.

Russ implemented the compiler change (dc7b2e9),

and updated ~every Go file in existence (08ca30b).

type PollServer struct { - cr, cw *chan *FD; // buffered >= 1 + cr, cw chan *FD; // buffered >= 1 pr, pw *os.FD; - pending *map[int64] *FD; + pending map[int64] *FD; poll *Pollster; // low-level OS hooks }

This rapid approach works well at a small scale.

14In mid-2009 the team prepared for the open source release.

Moved to their third version control system:

Mercurial, with Rietveld for code review.

The last Perforce commit (9e96f25, Oct 29) contained

10 November 2009: Go was released. (78c47c3)

There was a huge response to the release. The team was overwhelmed.

People sent changes from day one. The first non-Googler change:

commit 022e3ae2659491e519d392e266acd86223a510f4

Author: Kevin Ballard <kevin@sb.org>

Date: Tue Nov 10 20:04:14 2009 -0800

Fix go-mode.el to work on empty buffers

Fixes #8.

R=agl, agl1, rsc

https://golang.org/cl/153056In the first month, 32 people from outside Google contributed to Go.

The contribution process worked.

18The team continued to make big changes after the release.

But the process was now different, as they now had a community.

19On December 9th, Rob Pike sent the first public change proposal.

He proposed to remove semicolons at line endings.

go.dev/s/semicolon-proposal

The proposal was a "design doc" that included:

The design doc was shared with the community for feedback.

"Please read the proposal and think about its consequences.

We're pretty sure it makes the language nicer to use and sacrifices almost nothing in precision or safety."

The response was positive.

The proposal was implemented.

Most of the changes were made mechanically (thanks gofmt)).

This would be the shape of things to come.

21

The team was careful to curate the changes that made it into the language.

(Remember: "Wait for good design.")

There were many proposed changes and additions to Go.

As before, many more were declined than accepted.

Some fit with the project's goals, others did not.

An early accepted proposal:

x[lo:], x[:hi])And a declined proposal:

x[-n] == x[len(x)-n])At first, we did a poor job explaining the project's goals and development process.

This caused frustration. ("Why don't they accept my suggestions?")

It took us a while to articulate it:

Rob Pike's talk in October 2012

"Go at Google: Language Design in the Service of Software Engineering"

was the first thorough explanation of Go's raison d'être.

I wish we'd had this document written in 2009.

(But we couldn't have written it then.)

Read it, if you haven't already.

24What if Go has been open source from day one?

It may have been easier for the public to understand the project.

But it's not that simple:

Ideas are fragile in their early stages; they need to be nurtured before exposed to the world.

25Attempt to keep everyone in sync.

Great for early adopters and core developers.

27Contributors work at tip; users sync to weeklies.

Burden on users:

Version skew results because users are at different weeklies.

Skew fragments the community and slows adoption.

28March 2011: introduced releases every 1-2 months.

Keeps the community more in sync. Reduces churn.

Popular with users.

But skew still prevalent: adventurers and core devs still use weeklies (or tip!).

29A tool to mechanically update code to accommodate language and library changes.

gofix prog.go

Announced in May 2011.

Eases the burden of staying current.

Release notes now mostly say "run gofix."

Not a sed script. Works on the AST.

30

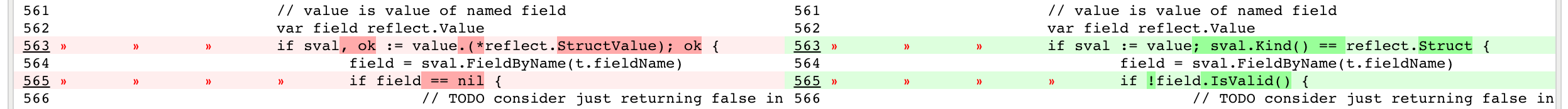

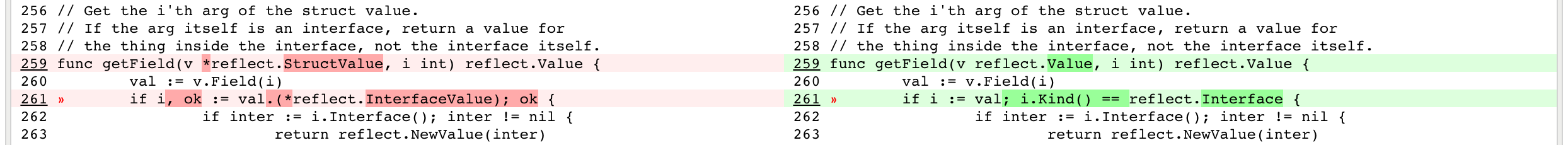

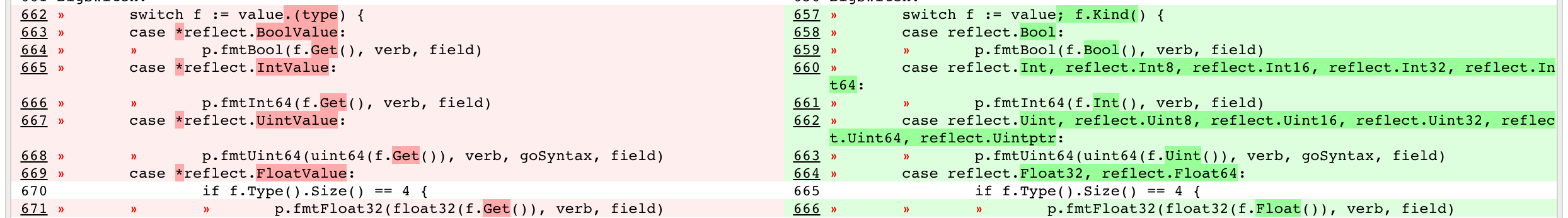

The reflect API was completely redesigned in 2011.

Gofix made most of the changes:

Gofix is no panacea.

As the root of the dependency graph, a programming language can suffer acutely from version skew.

The fundamental issue remains:

Code you write today may not compile tomorrow.

Some companies unwilling to bet on Go as they saw it as unstable.

32

Gofix makes changes very easy, and also makes it easy to experiment.

But it can't do everything.

Priorities: If change is easy, what change is important?

Wanted to make major changes to the language and libraries,

but this requires planning.

Decision: design and implement a stable version of Go, its libraries, and its tools.

33A specification of the language and libraries that will be supported for years.

Available as downloadable binary packages.

An opportunity to:

Polish and refine, not redesign.

35The team at Google prepared a detailed design document.

Implemented (but did not commit) many of the proposed changes.

Met for a week to discuss and refine the document (October 2011).

Presented the document to the community for discussion.

Community feedback essential in refining the document.

go.dev/blog/preview-of-go-version-1

36

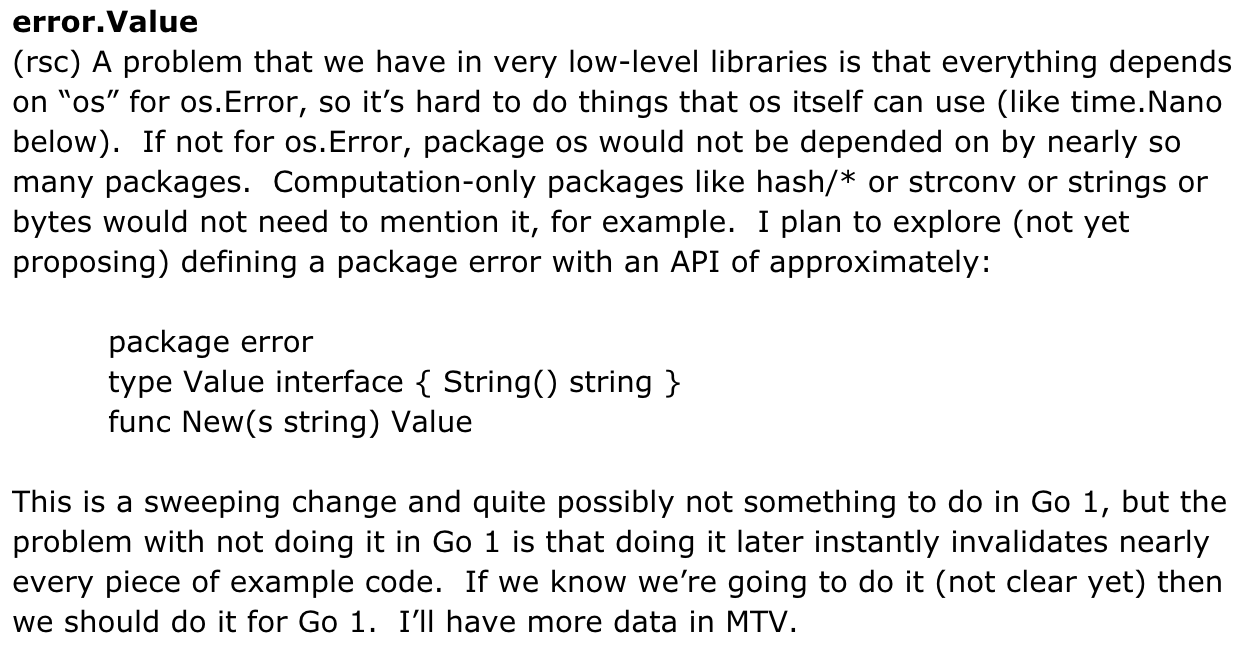

Before Go 1, there was no error type.

Instead, the os package provided an Error type:

package os

type Error interface {

String() string

}

References to os.Error were ubiquitous.

package io

type Reader interface {

Read(p []byte) (n int, err os.Error)

}

type Closer interface {

Close() os.Error

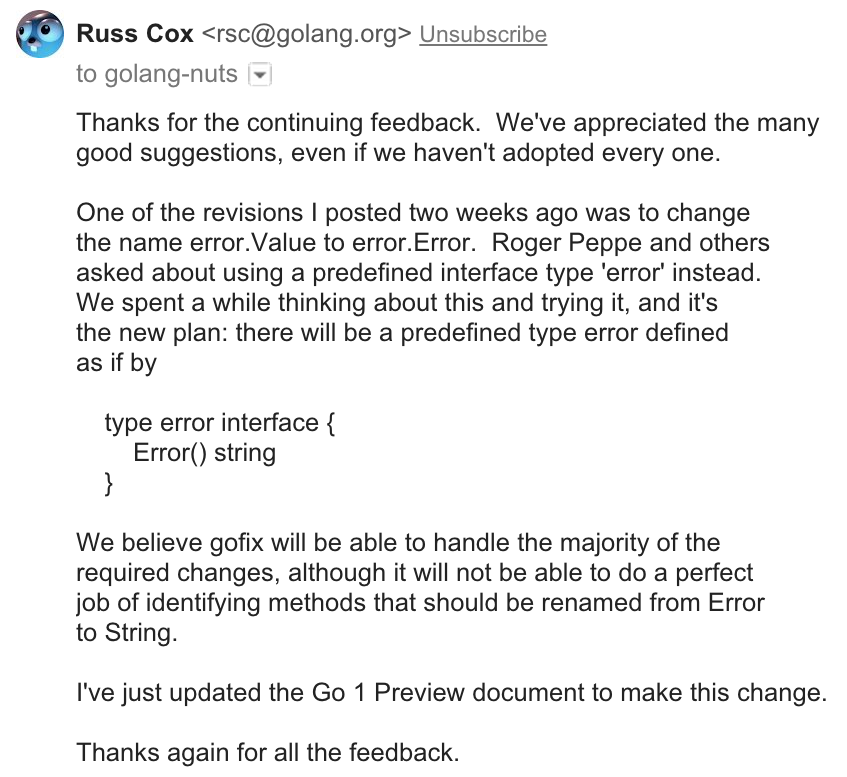

}Before the Go 1 meeting, Russ raised the issue in the design document:

At the meeting the team discussed the issue,

Russ presented data from his experiments with the change,

and we made a tentative decision:

On the list, the community made some keen suggestions:

Many of those suggestions were rolled into the Go 1 design document:

Create many new issues on the tracker.

Contributors nominate themselves to address specific issues.

Stop developing new features; prioritize stability.

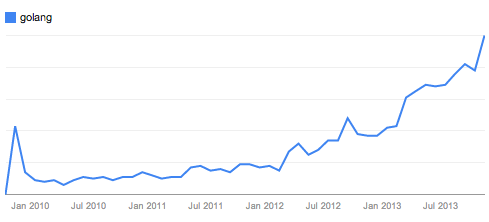

42The Go 1 release in March 2012 heralded a new era for the project.

Users appreciated the stability. Huge uptick in community growth.

Contributors focused on implementation, tools, and ecosystem.

43The next release was Go 1.1, more than a year after Go 1.

This is too long; switch to a 6-month release cycle.

Stuck to this plan for 1.2, 1.3, and 1.4, and we're (almost) on track for 1.5.

44Go's development process emphasizes up-front design.

The project has ~450 contributors and many committers from outside Google.

But most change proposals

(despite being driven by community feedback)

were made by the Go team at Google.

Why is this?

46The Go contribution guidelines are thorough on the code review process.

But on design, just this:

"Before undertaking to write something new for the Go project, send mail to the mailing list to discuss what you plan to do."

Does this describe the project's approach to design? Only superficially.

Successful proposals include design docs

that discuss rationale, tradeoffs, and implementation.

There is a gap in our documented process.

47Brad Fitzpatrick and I recently proposed a formal Change Proposal Process.

Its goals:

The new change process, in brief:

The new process is an experiment.

We're still discussing exactly how it should work.

I hope it will make Go's design process more accessible to the community.

50Go's design-driven process has served us well.

But as Go is more widely used,

the community needs a larger role in shaping its future.

With your help, we can make Go's next 5 years more spectacular than the last.

Andrew Gerrand